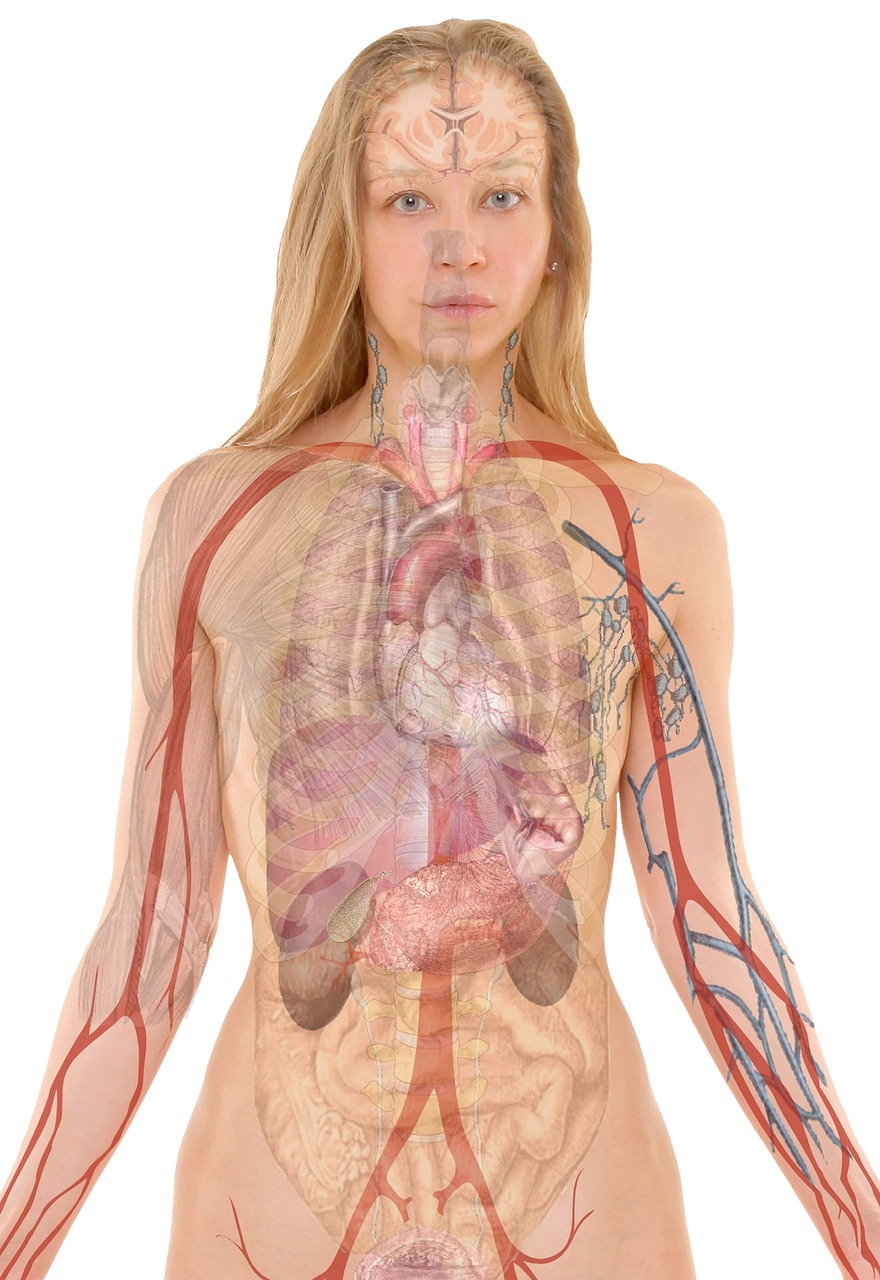

Traumatic experiences cast long shadows, often manifesting as persistent, debilitating memories that disrupt daily life. For millions worldwide, conditions like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are not merely psychological states but deeply engrained neural patterns, particularly within the brain's fear hub: the amygdala. Traditional therapies, while often effective, can be lengthy and challenging, prompting researchers to seek more precise and direct interventions.

Precision Neuroscience for PTSD Treatment

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) represents a debilitating condition affecting millions worldwide, characterized by intrusive memories, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors following exposure to a traumatic event. At its core, PTSD is a disorder of memory—specifically, the persistence of an overgeneralized, pathological fear memory. For decades, therapeutic interventions have largely focused on cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy, often with limited success for severe or refractory cases. However, the advent of sophisticated neuroscientific tools, particularly optogenetics, has opened an unprecedented window into understanding and potentially 'rewiring' the neural circuits underlying traumatic memories, offering a beacon of hope for a new generation of highly targeted treatments.

This article delves into a novel optogenetic approach that specifically targets the amygdala, a brain region critically involved in processing emotions, particularly fear. By harnessing the power of light to precisely control neuronal activity, researchers are beginning to unravel the intricate mechanisms of fear memory formation and, more importantly, develop strategies to selectively attenuate or even erase the emotional charge associated with traumatic experiences without necessarily obliterating the factual content of the memory itself.

Overview

The human brain's ability to form and retrieve memories is fundamental to our existence, yet this very capacity can become a source of profound suffering when memories of traumatic events persist and intrude into daily life. PTSD is distinct from normal fear responses because the fear becomes pathologically persistent, generalized, and resistant to extinction. Neuroimaging studies have consistently implicated the amygdala, particularly the basolateral amygdala (BLA), as a central hub in the neural circuitry of fear learning and expression. Dysfunction in this circuit, coupled with altered prefrontal cortex regulation, contributes significantly to the symptoms of PTSD.

Optogenetics offers a revolutionary method to investigate and manipulate these circuits with unprecedented spatial and temporal precision. By introducing light-sensitive proteins (opsins) into specific neuronal populations, researchers can activate or inhibit neurons simply by shining light on them. This technology moves beyond the broad strokes of pharmacological treatments or the relative imprecision of electrical stimulation, allowing for cell-type specific and circuit-specific interventions. The focus on the amygdala is strategic, given its established role in fear conditioning and its dense, well-characterized connectivity.

Principles & Laws

Neurobiology of Fear Memory

Fear conditioning, a classical model for studying traumatic memories, involves associating a neutral stimulus (e.g., a tone) with an aversive one (e.g., a mild foot shock). This association leads to a conditioned fear response, such as freezing behavior. The neural underpinning of this process is robustly localized to the amygdala. Sensory information about the conditioned stimulus (CS) and unconditioned stimulus (US) converges in the BLA. Within the BLA, specific ensembles of neurons undergo synaptic plasticity changes, notably long-term potentiation (LTP), strengthening the connections between neurons representing the CS and US. These strengthened connections allow the CS to subsequently activate BLA neurons, which then project to the central amygdala (CeA). The CeA, in turn, orchestrates the expression of fear responses via its projections to brainstem nuclei responsible for physiological and behavioral manifestations of fear (e.g., freezing, heart rate changes, hormonal release).

Crucially, memories are not static; they can be destabilized upon retrieval and then re-stabilized in a process called reconsolidation. During reconsolidation, a memory trace becomes labile and susceptible to modification. This brief window presents a therapeutic opportunity to weaken or update the traumatic memory trace.

Optogenetics Explained

Optogenetics relies on microbial opsins, such as Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) from green algae or Halorhodopsin (NpHR) from archaea. These proteins are light-gated ion channels or pumps that, when expressed in neurons, allow for their precise control. ChR2, for example, is a cation channel that opens in response to blue light, allowing positive ions to flow into the neuron, thereby depolarizing and activating it. NpHR, a chloride pump, responds to yellow light, causing hyperpolarization and inhibition of neuronal activity.

To deliver these opsins, researchers typically use viral vectors, most commonly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), which are genetically engineered to carry the opsin gene and deliver it into target neurons. Specific promoters can be incorporated into the viral vector to ensure the opsin is expressed only in particular cell types (e.g., excitatory neurons, inhibitory interneurons, or even neurons projecting to a specific area). Once expressed, fiber optic cables are implanted into the brain region of interest, allowing targeted delivery of light from an external LED or laser source to activate or inhibit the genetically modified neurons with millisecond precision.

Methods & Experiments

Research into optogenetic memory rewiring typically begins with animal models, predominantly rodents due to the ethical considerations and technical feasibility of direct brain interventions. A common experimental paradigm involves:

- Viral Vector Delivery: An AAV vector encoding the desired opsin (e.g., ChR2 for activation or NpHR for inhibition) under a cell-type specific promoter is stereotaxically injected into the target region of the amygdala, often the BLA or its specific sub-nuclei. This allows for gene expression and opsin integration into the neuronal membrane over several weeks.

- Fiber Optic Implantation: A thin optical fiber is implanted stereotaxically into the same amygdala region, precisely positioned to deliver light to the opsin-expressing neurons.

- Fear Conditioning: Animals undergo a fear conditioning protocol, typically involving pairings of a neutral auditory tone (CS) with a mild electrical foot shock (US). This establishes a robust fear memory.

- Optogenetic Intervention during Reconsolidation: Several days after fear conditioning, when the memory is consolidated, animals are re-exposed to the CS (e.g., the tone) to retrieve the fear memory. During this retrieval and subsequent reconsolidation window (which lasts for a few hours), light is delivered through the implanted fiber to activate or inhibit the specific amygdala neuronal populations. For instance, activating BLA neurons that encoded the original fear memory could strengthen it, while inhibiting them could weaken it. Crucially, researchers might target the specific 'engram' cells—the small ensemble of neurons that represent the memory trace—identified via activity-dependent genetic tagging methods.

- Behavioral Assessment: The animals' fear responses (e.g., freezing behavior to the tone) are assessed on subsequent days. A reduction in freezing compared to control groups indicates a successful attenuation of the fear memory.

- Electrophysiological and Histological Verification: After behavioral testing, brains are harvested to confirm accurate viral transduction, opsin expression, and fiber placement. Electrophysiological recordings can verify the functional impact of light stimulation on neuronal activity.

Innovative approaches also include 'designer' opsins that respond to different light wavelengths or exhibit different kinetics, allowing for even finer control. Furthermore, sophisticated imaging techniques like calcium imaging are sometimes integrated to visualize the activity of specific neuronal ensembles during memory manipulation.

Data & Results

Pioneering optogenetic studies in the amygdala have yielded remarkable results, demonstrating the feasibility of precise memory modulation. For instance, activating specific populations of BLA projection neurons during memory reconsolidation has been shown to enhance fear memory, while inhibiting them has attenuated it. More strikingly, some studies have demonstrated that activating newly formed, positive memory traces simultaneously with the retrieval of a negative memory can 'overwrite' or effectively reduce the emotional valence of the traumatic memory. This isn't merely suppressing the memory but actively changing its affective tag.

Researchers have also identified distinct roles for different neuronal subtypes within the amygdala. For example, activating somatostatin-positive (SOM+) interneurons in the BLA, which are known to inhibit principal neurons, during fear memory retrieval can effectively reduce fear expression by dampening the output of the fear circuit. Conversely, manipulating specific projections from the prefrontal cortex to the amygdala has shown promise in restoring top-down control over fear, a mechanism often impaired in PTSD.

A key finding is the specificity of the intervention. Unlike broad pharmacological agents, optogenetics can target the exact ensemble of neurons that forms the traumatic memory engram, or the specific circuit responsible for its pathological expression, leaving other memories and general cognitive functions intact. This precision suggests that it might be possible to selectively 'treat' the traumatic component of a memory without erasing the factual context, which is vital for maintaining an individual's sense of self and life history.

Applications & Innovations

The implications of optogenetic memory rewiring extend far beyond the laboratory. The primary and most direct application is the development of highly targeted therapies for PTSD, phobias, and other severe anxiety disorders. Imagine a future where, instead of years of therapy or daily medication, a brief, targeted light intervention could rebalance the emotional valence of a traumatic memory.

Potential Therapeutic Avenues:

- Targeted Memory Attenuation: Precisely weaken the pathological fear associations in the amygdala without affecting declarative memory.

- Reconsolidation Interference: Exploit the memory reconsolidation window to introduce novel, non-aversive information or to directly inhibit the circuits perpetuating fear.

- Circuit Rebalancing: Restore healthy excitatory/inhibitory balance within the amygdala and its interactions with other brain regions like the prefrontal cortex.

Beyond traumatic memories, this technology holds promise for a wide range of neurological and psychiatric conditions where specific neural circuits are dysregulated, including addiction, depression, and even neurodegenerative disorders. The concept of 'closed-loop systems,' where brain activity is monitored in real-time and optogenetic interventions are triggered adaptively based on pathological neural signatures, represents a cutting-edge innovation. Such systems could provide personalized, on-demand therapeutic modulation.

Key Figures

The field of optogenetics and its application to memory manipulation stands on the shoulders of several pioneering scientists. Karl Deisseroth and Gero Miesenböck are widely recognized for their foundational work in developing optogenetic tools, transforming our ability to precisely control neural activity with light. Their independent breakthroughs in genetically engineering neurons to express light-sensitive proteins opened the door for circuit-level analysis of brain function.

In the realm of fear memory research, luminaries such as Joseph LeDoux and Karim Nader have significantly advanced our understanding of the neural circuits underlying fear conditioning and the crucial role of memory reconsolidation. Their work provides the theoretical and empirical framework for identifying the precise targets and timing for optogenetic interventions aimed at 'rewiring' traumatic memories. The convergence of these fields—the precise tools of optogenetics with the detailed circuit maps of fear memory—has propelled the rapid progress seen in this exciting domain of human science.

Ethical & Societal Impact

The ability to manipulate memories raises profound ethical and societal questions. While the therapeutic potential is immense, the concept of 'rewiring' memories treads into morally complex territory:

- Identity and Authenticity: Our memories shape who we are. Altering traumatic memories, even for therapeutic benefit, could potentially impact an individual's sense of self, personal narrative, and authenticity.

- The Nature of Memory: What constitutes a 'good' or 'bad' memory? Who defines which memories are pathological enough to warrant intervention? There's a fine line between therapeutic modification and potential misuse for social engineering or erasing inconvenient truths.

- Informed Consent: Especially in individuals suffering from severe mental health conditions, ensuring truly informed consent for such a fundamental intervention becomes paramount.

- Potential for Misuse: The technology, if perfected, could theoretically be used for non-therapeutic purposes, raising concerns about coercion or manipulation.

- Slippery Slope: Could this lead to a society where uncomfortable memories are simply erased rather than processed and learned from?

These concerns necessitate careful ethical deliberation, public discourse, and the establishment of robust regulatory frameworks well in advance of widespread human application. Transparency and a focus on restoring healthy function, rather than simply erasing, will be crucial.

Current Challenges

Despite the immense promise, several significant challenges must be overcome before optogenetic memory rewiring can be translated into human clinical practice:

- Invasiveness: Current optogenetic approaches in animal models require intracranial surgery for viral vector delivery and fiber optic implantation. This level of invasiveness is a major hurdle for widespread human application, especially for a condition that affects a large population.

- Translational Gap: The complexity of the human brain, ethical constraints, and the sheer scale make direct translation from rodent models challenging. Identifying the precise human amygdala circuits and engrams involved in PTSD is still an active area of research.

- Long-term Safety and Efficacy: The long-term safety of viral vector delivery, sustained opsin expression, and chronic light exposure in the human brain is not yet fully understood. Potential immune responses or off-target effects remain concerns.

- Specificity and Off-target Effects: While highly specific, ensuring that only the pathological components of a memory are targeted without affecting healthy, adaptive aspects of memory or other cognitive functions is a formidable task. Memory engrams are often distributed across multiple brain regions.

- Non-invasive Light Delivery: Light penetration into brain tissue is limited. Developing non-invasive or minimally invasive methods to deliver light to deep brain structures like the amygdala is a major area of research.

Future Directions

The trajectory of optogenetic memory rewiring is exciting and rapidly evolving:

- Non-invasive Optogenetics: Research is ongoing to develop techniques for deeper light penetration, such as near-infrared light with upconversion nanoparticles, or through transcranial approaches that minimize invasiveness.

- Pharmacological Augmentation: Combining optogenetics with existing pharmacological agents could create synergistic effects, allowing for lower light power or less invasive interventions.

- Advanced Viral Vectors and Gene Editing: Next-generation viral vectors with improved cell-type specificity, reduced immunogenicity, and more efficient gene delivery will enhance safety and efficacy. CRISPR-Cas9-based gene editing tools could also offer new avenues for precise and lasting genetic modifications.

- Personalized Medicine: Leveraging advanced neuroimaging and computational modeling to map individual brain circuits and memory engrams could enable highly personalized optogenetic interventions tailored to each patient's unique pathology.

- Closed-Loop Neurofeedback: Integrating optogenetics with real-time brain activity monitoring (e.g., EEG, fMRI) would allow for adaptive, demand-driven interventions, where light stimulation is delivered only when specific pathological neural patterns are detected.

Conclusion

The prospect of rewiring traumatic memories using optogenetic approaches in the amygdala represents a paradigm shift in our understanding and treatment of PTSD and related disorders. By offering unprecedented precision in manipulating the very neural circuits that encode and express fear, this technology moves us closer to therapies that can selectively attenuate suffering without broadly impacting cognitive function. While significant ethical questions and technical challenges remain, the rapid pace of innovation in neuroscience suggests that a future where highly targeted, precision interventions can alleviate the burden of traumatic memories is not merely a distant dream but an increasingly tangible reality. The journey from the lab bench to the clinic will require rigorous scientific validation, careful ethical consideration, and collaborative effort, but the potential to restore peace for millions makes it a journey well worth taking.